PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

REFRAMING DEPARTURE

Curated by Aaliyah Ahmed , OCTH Head Curator

Reframing Departure, is an online exhibition that displays two politically charged narratives by artists Shana-Lee Ziervogel and Hafeez Floris. These narratives confront the inherited geographies shaped by colonial cartographers, apartheid planners and imperial image-makers. In this exhibition, both artists delve into the concept of migration, each presenting their unique and nuanced perspectives.

Hafeez Floris’s photographs capture the everyday movement of individuals transitioning from the urban outskirts to the city centre. This routine is deeply influenced by the history of Apartheid forced removals and the ongoing necessity to migrate for survival. Shana-Lee Ziervogel utilizes found imagery to address a different facet of displacement. Her collages reinterpret photographs often taken from a colonial viewpoint, of individuals who may have been forcibly removed from their native lands, or whose identities have been inaccurately portrayed. Through her artistic process, these subjects experience a different type of migration: a transformation in perception, shifting from the gaze of empire to a representation that is more authentic, intricate, and self-determined. Both Floris and Ziervogel explore the theme of migration. Floris emphasizes a physically demanding form of micro-migration, while Ziervogel examines the more subtle migration of ideas that takes place within our minds and imagination.

Floris’s photographic work arises from the daily commute between the margins and the centre, a journey influenced by the legacy of forced removals and Apartheid spatial planning. Cape Town stands out from other cities globally due to the displacement of the working class, who have been pushed further from the city centre despite the majority of their employment being located in the Central Business District (CBD). In contrast, in many other countries, the working class typically resides closer to their workplaces in the inner city, while affluent populations occupy the more distant suburbs. Floris’s photographic series, originally titled "Work before Work," goes beyond traditional themes of apartheid and inequality. It ventures into a more atmospheric space, where history intertwines with the present, not solely through policy or geography but also through emotion, gesture, and absence. What does it mean to yearn for a life that was never permitted to exist? His work alludes to the unseen labour of waking up before dawn to enter a city designed for exclusion. In Cape Town, where working-class communities continue to be marginalized, this journey transcends the physical. It becomes generational, emotional, and symbolic.

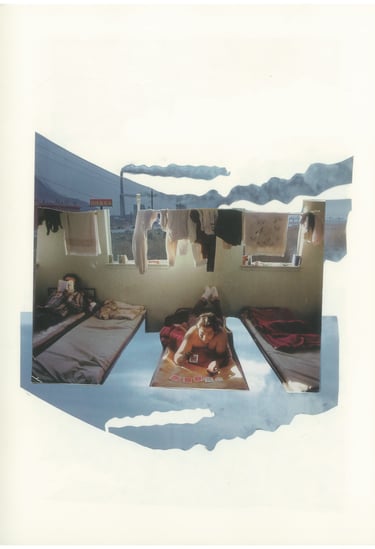

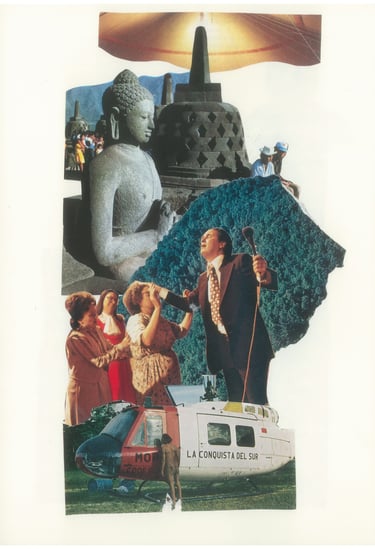

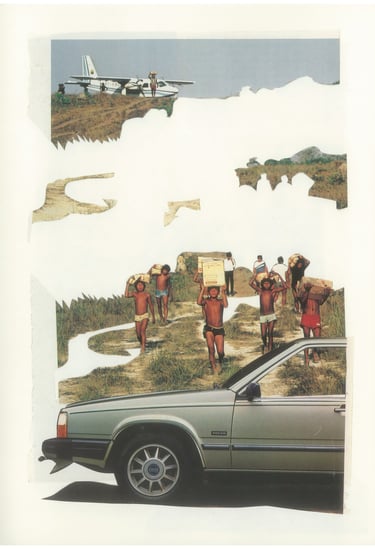

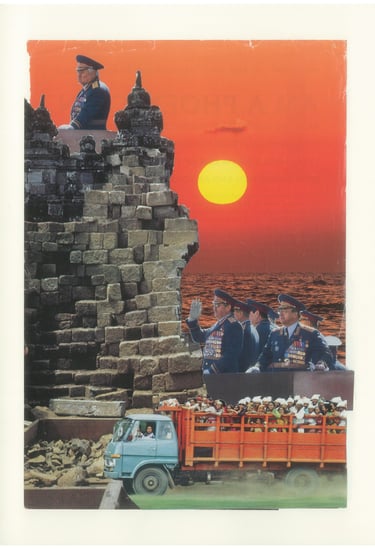

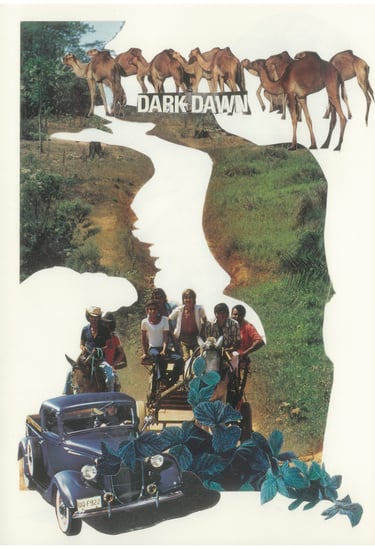

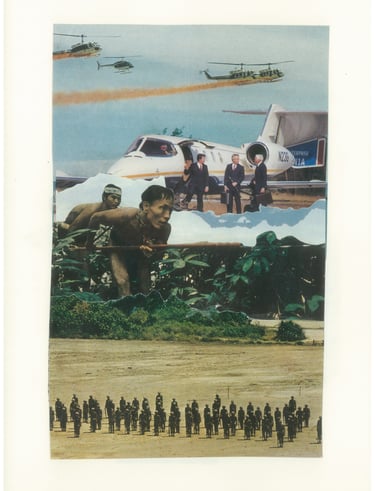

In parallel, Shana-Lee explores the visual legacies of empire through the medium of collage. By manipulating vintage National Geographic magazines, she cuts, rearranges, and reframes the images that once depicted the Global South through a colonial perspective. This act of cutting is not destructive, rather, it is liberating. These fragments expose how representation has functioned as a means of control, and how reassembly can transform into an act of reclamation. What starts as play evolves into protest, turning what was once spectacle into something more profound, authentic, and defiantly self-authored. The fragments she works with are not just leftovers but openings to new ways of thinking. Her reassembled landscapes and portraits challenge how people and places have been historically represented, offering glimpses into alternate versions that have not been shaped by empire.

This exhibition encourages viewers to see with fresh perspectives so that we can interrogate the lineage of power, to reflect on how we construct our inner landscapes, and to celebrate the radical act of envisioning home beyond the confines of what has been permitted.The past and present intertwine within these pieces, not as distinct eras, but as overlapping wounds, with apartheid policies reflected in contemporary urban planning, and colonial perspectives echoed in modern media and memory.

ONLINE EXHIBITION

Check out our virtual gallery

HAFEEZ FLORIS

Dividing Light

Veil of Silence

Stripes in motion

Distance Measured

Echoes of Transit

Burden of Dusk

City Mirage

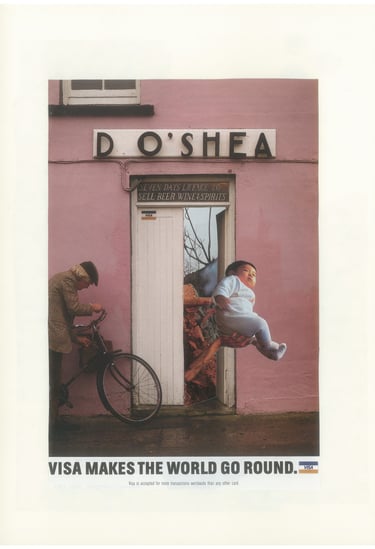

SHANA-LEE ZIERVOGEL

Free them through gospel

Captivate me with your games

Visa makes the world go round

Nourish my dependancy

Fires of Freedom

Dark Dawn

Mineral Occupation

The Archives

Cape Town is considered to be South Africa’s most segregated city due its social composition and spatial form are rooted in its colonial and apartheid history. A history where racial discrimination was extreme between 1948-1994. It is a city that holds extremely wealthy suburbs which offer exceptional amenities, beautiful scenery and access to opportunities to move up the social ladder but is also juxtaposed with extreme poverty, inhospitable settlements that are often neglected economically, politically and socially despite its deep history. Places such as District Six, Mitchells Plain and Khayelitsha.

Cape Town's crowded informal settlements around the City Bowl showcase marginalized communities creating space in cities that fail to accommodate them. The city's unique topography and biodiversity hotspot lead to housing shortages, segregation, and special nature reserves. The Atlantic Seaboards attract wealthy international homebuyers and tourists, inflating house prices and affecting the local economy.

Its social and spatial and social divisions are rooted in the long history of colonial rule and Apartheid. The Group Areas Act of 1950, a key apartheid law, enforced racial segregation, making race synonymous with socio-economic status. Despite its abolishment in 1994, urban inequalities persist, with economic growth and affirmative action not eradicating these divides.

When the National Party came into power in 1948, it developed and formalised decades of racial exclusion through laws such as the Group Areas Act. Residential Zones were assigned on the basis of race, with the central urban areas reserved for white citizens while Black, Coloured and Indian communities were pushed to peripheral sites.

In Cape Town, this destroyed established communities and displaced around 150,000 people by the late 1960s - including 55,000 residents uprooted from District Six. Peripheral areas such as Mitchells Plain (created in the 1970s) and Khayelitsha (created in the 1980s) were designed to house displaced Coloured and Black communities far from the city centre, with minimal planning for jobs, education and public services.

This geographical exclusion continues to profoundly affect Cape Town’s working class population- who often find themselves far from quality schools, jobs and services. Meanwhile commercial success of the central business district (CBD) and surrounding tourist hubs has increased property prices leading to gentrification that displaces lower-income households. This process furthers the already vast gap of inequality between the rich and the poor, making it harder for vulnerable communities to thrive.

This legacy of Apartheid planning forces most of Cape Town’s working-class population - including hospital workers, shop assistants, security staff and cleaners - to endure long, unsafe and emotionally taxing daily commutes from distant townships. Municipal reports estimate that poor households spend up to 40 % of their disposable income on transport. Many residents remain trapped in these areas due to restrictions on the resale of government housing within the first ten years, compounded by the delays of receiving title deeds.

These spatial barriers reinforce the racial and class inequalities established under Apartheid. Living far from economic opportunities makes it extremely difficult if not impossible to break cycles of poverty, and race remains closely linked to spatial exclusion.

These burdens fall unevenly across the population, with gender playing a significant role in shaping experiences of mobility and safety. Women and gender- diverse people face heightened vulnerability on the public transport and public spaces. Harassment is common: many women report avoiding taxis dominated by male passengers , while verbal abuse and sexual harassment are frequent. Fear of sexual violence shapes how women travel influencing their routes, times of travel and transport choices. Walking alone can also be dangerous , forcing many women to travel in groups or seek costly alternatives like Uber, Bolt, In drive etc. For young children in townships affected by gang violence, the journey to school itself can become a daily risk, limiting educational opportunities and future prospects.

Beyond the physical hardships of commuting, the emotional and psychological effects of forced removals and ongoing spatial inequality are profound. Many families continue to carry the trauma of displacement, having been uprooted from their close-knit communities and ancestral homes. This disconnection from place and history contributes to a sense of loss, alienation, and fractured identity. The stress of navigating hostile urban environments while struggling with economic insecurity exacerbates mental health challenges , particularly for women and children.

These emotional impacts reverberate across generations, shaping how many residents understand their place in the city today.

Despite these systemic barriers, communities continue to resist and survive in creative ways. Grassroots housing activism, informal transport networks, and everyday acts of care and solidarity allow residents to adapt and push back against spatial injustice. Such efforts challenge narratives of helplessness and reveal the resilience and strength of marginalised communities in Cape Town.

To understand Cape Town’s ongoing spatial inequality is to recognise it not merely as a legacy of the past, but as a living system that still structures opportunity, risk, and well-being. Archival work plays a vital role in centring the voices of those displaced and marginalised — reminding us that these histories are far from over, and that imagining more just urban futures depends on remembering them.

Research by Zoku Mgoduka-Horn and cross-checked by Kauthar Amlay

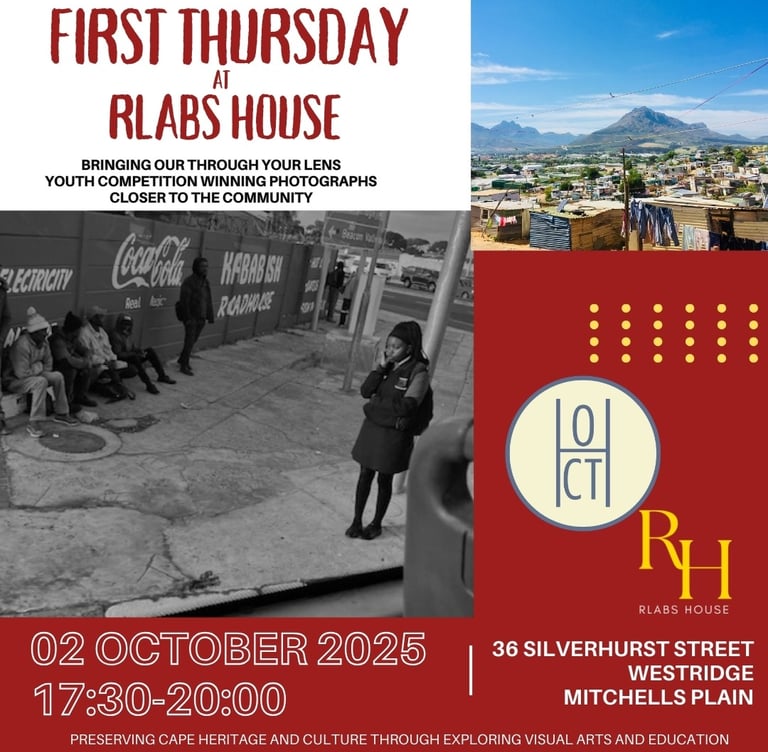

YOUTH INITIATIVE: THROUGH YOUR LENS

THE WINNING PHOTOS WILL BE AT RLABS HOUSE AND GALLERY IN MITCHELLS PLAIN FOR A POP-UP ON FIRST THURSDAY

As we share similar values and a mission, together with RLABS House and Gallery, we aim to inspire the youth and the broader community by instilling hope for the future. We believe that bringing the winning photos of the learners along with DARL: Mitchells Plain closer to the community, allows residents and visitors to engage with and appreciate their history and heritage with more hope. The Digital Archive Research Library (DARL) delves into the rich cultural and social fabric of Mitchells Plain, emphasizing it's gems of history that often go untold. This event serves as a platform to be inspired and learn as well as an opportunity for the community and youth to be empowered by coming together, to celebrate their heritage, and redefine the narrative surrounding Mitchells Plain by capturing the essence of community, its resilience and spirit.

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions