PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

EKSÊ! Echoes of Self

Artists: Kimberley Titus & Gary Frier

4-7 July 2024

Bo-Kaap Deli, Bo Kaap

CURATORIAL

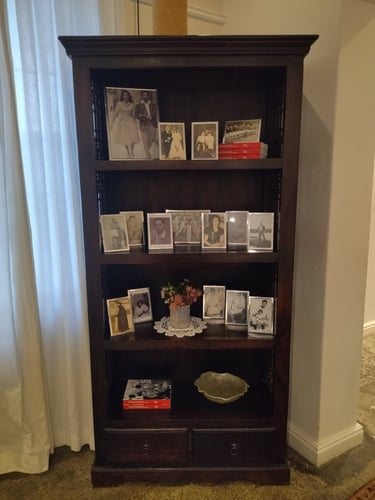

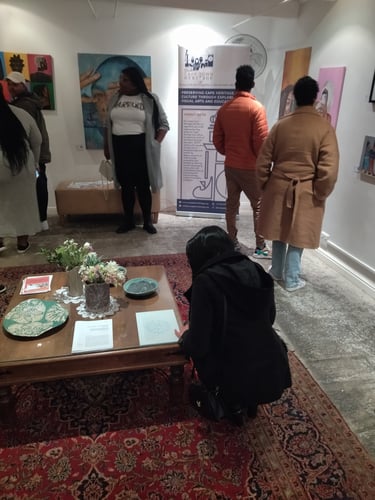

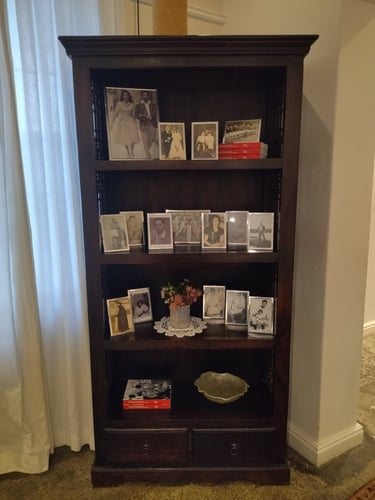

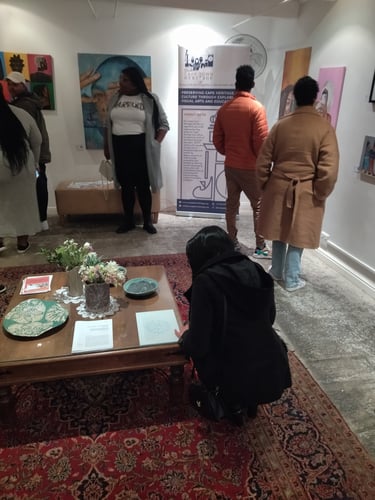

Set in Cape Town's favourite breakfast spot, Bokaap Deli, the exhibition was held at their Events space. Being transformed from a regular crowded room into a showcase-style Art Gallery. Natural light streaming in illuminated the space, highlighting the vibrant artwork that reflected the artists' expression of self-identity. Nadia Kamies' portraiture was proudly and artfully arranged in a cabinet, reminiscent of the old showcase-style cabinets in our mother and grandmother's houses, invoking a sense of nostalgia and remembrance. The paintings were arranged in a staggered formation to feel intimate and relaxed for a more cozy and welcoming atmosphere. OCTH’s “EKSÊ! Echoes of Self” through time and space, highlights the noticeable evolution in culture, leading to the emergence of various subcultures and creating opportunities for new possibilities for future generations. Showing that this evolution in culture has paved the way for the flourishing of diverse subcultures, each bringing its unique perspectives and contributions to the tapestry of society and communities as whole.

In examining communities formed by the amalgamation of diverse individuals, it is clear that a single homogeneous culture does not exist. Culture is a fluid entity, subject to constant evolution as communities continuously mold and redefine cultural concepts, notably in the context of "colouredness."

The concept of "colouredness" or the "coloured experience" holds various implications that have undergone notable transformations in the last couple of centuries and most noticeably the last 3 decades. Our perception of cultural identity is shaped by internal and external elements such as the era and political climate of our birth, both on a local and global scale, the cultural milieu in which we were raised, and our social surroundings, among others. This is evident with the two artists featured in our exhibition, Kimberley Titus and Gary Frier, who come from distinct generations and regions within the Western Cape. These factors have shaped Titus and Frier's perception of cultural identity, shaping their perspective through which they see the world. As a result, these influences are reflected in their artworks and the way they portray their lived experiences. Consequently, we observe two distinct perspectives about culture and how each chooses to represent it visually.

There is a noticeable evolution in culture, leading to the emergence of various subcultures and creating opportunities for new possibilities for future generations. This evolution in culture has paved the way for the flourishing of diverse subcultures, each bringing its unique perspectives and contributions to the tapestry of society and communities as whole.

Kimberley Titus, born in Strandfontein, finds joy and beauty in the world around her and aims to engage with the audience, encouraging them to contemplate their own life experiences. She aims to capture the essence of the African community as a whole through the use of vivid and striking colours in her paintings. She delves into culture by exploring her own identity, recognizing that her cultural heritage is an intrinsic part of her being. Embracing the rich tapestry of her cultural background, with roots in Namibia, she immerses herself in the traditions, customs, and stories passed down through generations. With each discovery, she feels a deep sense of connection to her roots and a profound appreciation for the diverse perspectives that shape her worldview. Through this journey of self-discovery, she not only celebrates her heritage, but also gains a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of her culture, fostering a sense of a new cultural identity. In honouring her past, she is empowered to confidently navigate the complexities of the present and envision a future where diversity is not only acknowledged, but also celebrated as a source of strength and beauty. Through her representations, we perceive a contemporary perspective on cultural experiences as a millennial, exploring the physical manifestations of culture.

Gary Frier, born in Kuilsriver, is an artist and art therapy facilitator. Frier uses different found objects and discarded materials in his portraits of people he has come across in his life as a facilitator. While in the Northern Cape, he felt a strong connection and curiosity towards individuals who embraced solitude in the vastness of their environment. He also incorporates elements from the First Nation Khoisan mythology into his artwork that he believes no longer remains in the new generations of indigenous nations who were disenfranchised by spatial apartheid planning. By drawing inspiration from ancient myths and folklore, Frier's artwork aims to shed light on the profound impact that culture and mythology have on promoting social well-being and unity within society. Through his creations, he weaves together narratives that transcend time and space, inviting viewers to contemplate the timeless wisdom and universal truths embedded in these stories.

Both Titus and Frier’s artistic endeavours serve as a bridge connecting the past to the present, fostering a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of human experiences and beliefs that shape our collective identity. In a world often marked by divisions, their work stands as a testament to the power of heritage and art that inspires empathy, understanding, and a shared sense of humanity across diverse cultures and traditions. The two artists anchor themselves in distinct temporal contexts; Kimberley asserts a specific viewpoint, while Frier’s interpretation of culture is characterized by fluidity and introspection. The goal of this exhibition is to explore the core of various cultural experiences that are both timeless and rooted in different eras. It delves into how these cultural identities shape fresh cultural encounters. Both artists draw inspiration from their distinct experiences, utilizing their artwork to enrich a communal discourse centred on themes of hope, tradition, resilience, and societal betterment. As visitors engage with the exhibition, they are encouraged to contemplate the intersections of past, present, and future cultural identities and landscapes.

Nadia Kamies, writer and academic author on the subject of “Coloured” Identity shares her personal family archive. The personal portraits serve as a time capsule, capturing the essence of what it meant to be a person of colour in a former era and the intricate ways in which this history intertwines with one's sense of self. It meticulously documents the stories, struggles, and triumphs of those who navigated a world coloured by prejudice and discrimination, offering a poignant glimpse into how experiences of the past continue to shape and inform our present identities. As we delve into these preserved memories, we are reminded of the resilience, dignity, and spirit of community that have long been hallmarks of the "coloured" experience, inspiring us to honour the past while charting a course towards a more inclusive and equitable future.

The preserved portraiture images by Nadia Kamies intricately capture the narratives, challenges, and victories of individuals navigating a world tainted by bias and inequality. These images offer a poignant insight into how historical encounters continue to influence our present identities. Portraiture remains a potent medium, serving as profound historical artifacts that narrate the tales of past societies while shaping the trajectory of history and culture. Initially appearing as mere depictions of individuals, a closer examination reveals invaluable clues that assist in unraveling compelling historical stories.

Portraits not only functioned as a form of defiance against colonization but also as a cultural weapon against segregation. Kamies's photographs stand as invaluable historical reservoirs. With a discerning focus on the past, she frequently discovers inspiration and enlightenment in history, drawing upon the teachings and experiences of bygone epochs. The personal family archival photos and portraits act as a visual representation of culture through time and serve as a cultural memory, offering valuable and insightful information about history, about ancestors and about connections. Nadia Kamies sharing her personal memories helps us comprehend the past along with the values and norms of the “coloured” experience. It additionally generates a sense of collective identity and is a way of conveying a cultural heritage to individuals who are unfamiliar with it.

All three participants of this exhibition share their subjective experiences of their “coloured experience” and explain what has influenced them and shaped their understanding of who they are today. Kamies, with a keen eye on the past, often finds inspiration and wisdom in history, drawing from the lessons and experiences of bygone eras. Titus, on the other hand, is a visionary, constantly gazing towards the future with boundless curiosity and optimism, seeking to innovate and create a better tomorrow. Frier, with a unique perspective, delves into the timeless aspects of culture that resonate across generations, uncovering the threads that connect us to our roots and shape our collective identity. Together, these three individuals offer a multifaceted view of the world, each bringing a valuable contribution to our understanding of heritage, time, progress, and the enduring essence of culture.

While exploring the exhibition, visitors are prompted to contemplate their life experiences and how their own heritage and cultural identity has been influenced over time.

The Archives

HISTORY OF "COLOURED" COMMUNITIES

The Free Blacks or ‘Free Burghers of Colour’ were first listed in the first three decades of of the 19th Century in the Cape colony records by early segregationists formed the first communities who, having been freeborn or manumitted from enslavement, would come to be the first “coloured” communities. These included, but were not limited to manumitted slaves, Arab, Chinese, Indian and Indonesians, who arrived as political exiles, merchants, seamen, adventurers and travellers, as well as the Mardijkers (the Ambonese-Portuguese VOC soldiers who, culturally having been influenced by Muslim culture were mistakenly listed as Muslims, but were in fact Christian). Other European people within this group choose to be part of the communities, not by class or by accident but in the spirit of non-conformist rebellion against the colonial paradigm. From these self-formed communities, including indigenous peoples and offspring of transient relationships between the groups, endemic in seaports around the world formed what would come to be classified as the ‘Coloured’ people of the Cape.

With the passing of Ordinance 50 of 1828, outlining the abolition of slavery, saw enslaved peoples in the colony gaining financial independence and freedom of movement (at least on record) seeing most manumitted from 1834-35, with the ordinance prescribing a period of 4 years of “apprenticeship” in their trades which was to all intents and purposes under the same conditions as under enslavement, in December 1838, the last slaves were granted their freedom.

Gaining property and being skilled tradesmen, the formerly enslaved indigenous population, with the passing of Ordinance 50, gradually formed their own communities within the Cape society. A vibrant mixture of cultures and traditions, their descendants would collectively be labelled as Afrikaner, meaning persons born in South Africa, the term later co opted by white South Africans who used the language of Afrikaans to distinguish themselves from their English speaking counterparts in the move for independence from British rule. This group of people, the non white South Africans who did not fall within the categories outlined by Blumenbach’s (disproved) race theory from the sixteenth century, which was widely adopted by Europeans to justify the subjugations end exploitation of non-European peoples and lands. The five categories, being each paired with a colour, were Caucasian (taken to define Europeans, but was appropriated from an ethnic group: the Circassians) - White, Negroid (reducing all of African origin to this label) - Black, Indian (South Asian) - Red, Mongoloid (East Asian)- Yellow, and Malay (South East Asian and Pacific Island peoples) - Brown. This reductive system of characterization was unable to define the multifaceted group of people and they were deemed simply “Coloured”.

Stripped of their identity and relegated to the margins of society this group found self affirming message in the Black Consciousness movement. Identifying as Black in protest to the caste system of Apartheid race classification in the 1960’s, and reemerging with the Hip Hop Movement of Cape Town in the 1990’s, led by figures such as Reddy D, Prophets of Da City and Black Noise. This connected street culture and ‘Knowledge of Self’ - the core philosophy of Hip Hop, with the spiritual self exploration and self defined identity. In the broad sense this was confined to spoken word practice of MC’ing or rapping; performing poetry to music. While the visual arts were not widely explored in this sense, or at least given the platform within popular culture.

Did you know?

The indigenous Khoe cosmology describes the creation of the world through anthropomorphic celestial entities. As recorded in the manuscripts by Lloyd and Bleek, these texts give an insight into the way the indigenous peoples viewed the world and their interaction with it. They valued cultivation, but in concert with the natural world, aligning themselves with the seasonal transitions and marking temporal movements with the cycles of the moon. Viewing the world through a system of dualities, favouring that which is contributive to wholistic society as opposed to the destructive and extractive. The spiritual realm was not seen something wholly separate from their corporeal existence. This aligns with the contemporary notion of sustainable living, as many indigenous practices do, if they are not the originators, repackaged and commodified in our present day.

Video by Thuraiyaa Isaacs

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions