PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

A Glimpse Between Memoirs: Childhood Nostalgia

Artists: Shaunez Benting and Whaleed Ahjum

February 2024

Bo-Kaap Cultural Hub, Bo-Kaap (in collaboration)

Set in the transformed space of the Bo-Kaap Cultural Hub Oemie Room, Shaunez Benting and Whaleed Ahjum took us through a memoir of their childhoods, offering profound insight into their heritage, traditions, and cultural backgrounds within a Cape Malay context. The Oemie Room was transformed from a workshop space to an art gallery, effectively capturing the audiences’ attention through sight and sound, with voice-over memories being played through the sound system, and projected videos of the artists speaking about their art practice

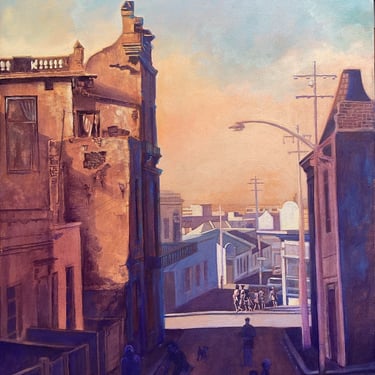

Through the medium of fine art, these artists articulated and invoked a sense of yearning and a reminder of crucial spaces and memories, as experienced through childhood to adulthood. Benting focused on spaces, depicting fond memories he and his peers occupied for play during a tumultuous time in South Africa’s history - Apartheid. Ahjum’s work expressed a deeply personal account of a family history supplemented by archival research into his own heritage and maternal lineage.

By revisiting the historical tapestry of South Africa, encompassing both its triumphs and challenges, the artists craft a narrative that is both intricate and deeply personal. They serve as poignant reminders of the historical struggles endured by our predecessors and their strength, shaping our present-day sense of community.

Nostalgia plays a crucial role in comprehending how individual and organisational identities are shaped, as it serves as a tool for preserving a collective sense of socio-historic continuity, as well as a mechanism for resisting hegemonic influences and providing a form of defiance. This approach entrusts us with the responsibility of shaping our own narratives and determining how we wish to be perceived in the archives of history. The artists choose to depict cherished memories from their childhood or collective experiences, infusing their beautiful creations with rich context in a delightful way.

Nostalgia is commonly depicted as a somber soul condition; however, it can also serve as a reflection for youthful self-exploration and enlightenment. This exhibition underscores the significance of nostalgia and heritage, harnessing this sentiment to craft a sense of "collective self-authorship." A collective self-authorship holds significance as it empowers communities that have historically been misrepresented and continue to grapple with the repercussions of such misrepresentation. Benting and Ahjam opt to utilize historical artifacts to examine their current circumstances and honour their ancestors.

As both artists share Cape Malay heritage, their rich cultural history allows them to connect with their compelling past. Benting delves into his childhood recollections, opting to portray the marginalized spaces and communities that he grew up in, which flourished despite enduring an oppressive regime. By delving into past imagery, Benting accentuates the enduring cultural vibrancy that remains pertinent in the contemporary era. Ahjum explores his South East Asian roots and how it intersects with the Cape Malay culture and heritage in Cape Town. Rediscovering and re-establishing a deeper connection with his cultural roots and heritage. We accompany Benting and Ahjum as they navigate through their memories, intertwining shared cultural references that resonate universally. Benting reflects on the innocent moments of his childhood, capturing the essence of growing up in District Six and various other locales. Ahjum, in his quest to embrace his lineage, gazes upon the tapestry woven with the traditions, legacies, and customs of his forebears.

Reprisal: August - September 2025

The Archives

RESEARCHERS &

WRITTEN BY:

Yunus Ogier

Zoku Mgoduka-Horn

The Dutch East Indian Company and Slavery

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was a Dutch enterprise that operated commercial and slave trading in the East Indies. Its purpose was to increase profit by establishing colonies, with welfare being seldom a concern. The Cape was suggested as a refreshment station by two survivors of the Haarlem shipwreck Janssen and Proot in 1648. The Cape Colony was governed by an executive council, the Heren XVII, and a governor-general and Council of India in the East Indies. Until 1732, the region was governed by both the Heren XVII in the Netherlands and the Council of India in Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia). Burghers (who were former employees of the VOC) in the Cape held rights to some extent, such as not being enslaved and owning land. However, they had to do military service, take an oath of loyalty to the States-General, and the VOC could ban troublesome burghers. Class differences were evident, with rich burghers and poor burghers looking down on each other. People of color and slaves received heavier sentences for the same crimes. The idea of equal rights took time to take root, with equality and rights gradually extending to white middle-class men, white women, and all people from the mid-20th century onwards.

The introduction of slavery at the Cape of Good Hope

On the 28th of March 1658, the first shipment of slaves arrived at the Cape of Good Hope aboard the Amersfoot; a Dutch vessel which had managed to hijack a Portuguese ship carrying slaves bound for Brazil just off the Angolan coast in the Atlantic Sea. The motive was clear: to bring slaves to the Cape to increase the labour force, thus marking the start of the slave era at the Cape Colony during the 17th century. The period 1658 to 1807 proved to be a lucrative time for slave trading at the Cape as it saw the arrival of people coming from Africa and Asia and converging upon the Cape in what must have been a highly diverse mixing pot of cultures.

When the Dutch first arrived at the Cape in 1652, the indigenous inhabitants on the landscape were the KhoiKhoi and the San people who practiced pastoralism and hunter-gathering respectfully as the Cape had an abundance of free roaming livestock.The Dutch opened up a refreshment station at the Cape to supply passing ships with fresh goods. However, what was needed was fruit and vegetables and this led the Dutch East India Company (VOC -Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) to initiate farming practices within the region to allow for a steady supply of produce for passing vessels. The ever growing Free Burghers were in the service of supplying these goods to the VOC, but needed aid in working the farms and therefore requested slaves to assist them. A mandate by the Dutch government forbade the VOC to enslave indigenous groups, therefore slaves had to be sourced elsewhere. So began the numerous expeditions of the VOC in their efforts to boost the slave population. In addition to the Amersfoot acquiring slaves and bringing them to the Cape, other slave expeditions were organized by the VOC, notably in the Indian ocean area where they were imported from India, Indonesia, the African east coast and Madagascar. The ten year period from 1660 to 1670 saw a proliferation of imports from the Indian region (Bengal, Malabar and Coromandel) where the highest number of slaves from this region were recorded. Beginning in 1673, the ship Johanna Catharina was dispatched to Madagascar to procure enslaved people, and in 1784, the Meermin became the last vessel to transport slaves to the Cape, ending the 126 year long slave trade.

The domestic slave market

The VOC held a certain level of control over the domestic slave market from 1658 to 1792, and even if they were the main sponsors of expeditions to procure slaves (for their lodges), the VOC would rarely act as a seller within the market. A remark from 1685 in regards to lodge slaves read: "Perfect order will prevail over the slaves of the Company: the lodge slaves may never be exchanged, sold, alienated or exported by anybody no matter what his station”.

The primary focus of the slave market at the Cape was to ensure that prospective buyers were able to purchase slaves when they arrived. At the colony there were three main categories of buyers:

1) VOC officials who managed the ocean trade network and who were themselves slave owners.

2) The urbanised “Free Blacks”, Chinese ex-convicts, ex-slaves and a mixture of Indian and Indonesian political exiles. The political exiles utilised the domestic slave market to free their kind, in a way using the very act of oppression and turning it into some kind of resistance.

3) The final group who were purchasing slaves were the Burghers, who were dominated by a more patriarchal social system and were the ones who initiated the need for more slaves at the Cape for farm assistance.

Cape Malay/Muslim Community

In 1682, the Cape Colony was on its way to becoming a hub of slaves who were politically exiled from their homelands. These were so-called unruly tribes from Indonesia and the first muslim slave to arrive was Ibrahim van Batavia (Jakarta), who was brought in towards the end of the 17th century. The Indonesian archipelago has over 17000 islands, with the center Batavia (currently Jakarta) sitting in Jawa. The other major islands are Sumatra, Borneo (shared with Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei) and Sulawesi. All these islands hold their own religious beliefs and cultural customs, which meant that slaves arriving from these areas (Batavia and Sulawesi -where Makassar is located) came with their own set of cultural traits. This, in addition to the groups coming from the Indian ocean region and east African coast, meant that the Cape was now a culturally rich and diverse colony, a colony that was not mirrored anywhere else on the continent.

This concentration of ethnically and culturally diverse groups also have led to the rapid spread of Islam in the area. Muslims during this period were prohibited from practicing their faith in public due to Dutch colonial law, however, they were allowed to practice in the privacy of their homes. As a result, the slaves (of the Islamic faith) were able to disconnect from their oppressed identity and shift it towards an identity of faith. In doing so, they cultivated a spiritual persona that existed beyond the confines of enslavement, a persona that offered resilience in the time of physical bondage. The practice of intermarriage (or unions, as Islamic marriage was not recognized) with muslim slaves increased their numbers and formed a sense of community. Islam was not only an abstract form of religion being practiced, it became a beacon of hope to dislocated diasporic groups who found a new identity in the form of Islam.

One other crucial element also led to Islam making an imprint at the colony in the early days. Slaves that were baptized were not always brought into the fold of Christianity, as ultimately, a slave had to remain a slave. George Champion, a missionary to the Cape during the 19th century remarked upon this peculiar phenomenon. He noticed that most of the converts to Islam were slaves who were from African and Asian descent and therefore deemed as inferior to the white Christian. If a slave was to be recognized as inferior, then there would be no way for him to be admitted into a white man's religion, and Christianity, coming from Europe, appeared to be the pinnacle of colonizer authority. But the bigotry of colonizers soon turned against them, and the Muslims utilized this to welcome slaves into their community. Therefore, this pattern of slaves converting to Islam was not purely a spiritual accomplishment that the slaves wanted to achieve, but more as means to be accepted into society. Political exiles, most notably Sheikh Yusuf, also welcomed rejected Christians into the Muslim faith—turning exclusion into belonging. By 1834, nearly a third of all slaves at the Cape had embraced Islam, marking both a quiet resistance and a powerful redefinition of identity in the face of oppression.

Slavery was not static but a growing complex interactional process of patterned behavior. Control was exercised through the suppression of slave culture, with enslaved people not allowed to keep their own names. Children were given names after their place of birth, people of their capture, religious mythology figures, or the month of the year. Slaves were employed in various aspects of life, including digging canals, building fortifications, and working the harbor- however this physical labour was only a means by which the VOC could exploit to tighten their grip on the colony, where more slaves equals more work being done therefore more economic growth. They served as woodcutters, water carriers, bricklayers, lime-burners, masons, carpenters, fishermen, porters, and street sweepers and yet were frequently treated as less than human.

The accommodations at the VOC’s slave lodge were subhumane, with their housing often being dark, wet, and dirty. Then to add insult to injury, the VOC enforced religious conditions, requiring all slaves in the Slave Lodge to be baptized within seven days of birth. By 1775, 1715 children from the Lodge were baptized, with approximately two-thirds of all slave children living in the Lodge. Enslaved children also received religious instruction at the Lodge school, which was established in 1658 to teach Dutch and Christian religion. The Dutch Reformed Church was recognized by the VOC, but the spread of Christianity to both freemen and enslaved people often faced contradictions. The Dutch Reformed Synod of Dordt declared in 1621 that enslaved people should have equal rights to other Christians and not be sold to the power of heathens. This incentive for enslaved people to get baptized aimed at attaining freedom became harder to achieve. However, children born to enslaved persons and a white father owned by the VOC could purchase their freedom as adults, provided they were baptized in The Dutch Reformed Church and could speak Dutch.

Cultural practices

Slavery introduced various cultural practices, and for those enslaved individuals who were not part of the Islamic faith, there was a pressing need to establish a sense of community through shared identity. The ratiep (ratib) is a Sufi devotional ritual where the participants would chant religious phrases in the remembrance (dhikr) of God (Allah). Often at times these rituals will have groups of men performing and going into trance like states from the chanting and drumming, where they would pierce themselves with daggers and swords, but causing no harm. According to some scholars, the ratiep has its origins in southeastern Asia and may not be directly related to Islam, but acted as a practice to help slaves identify with something, if anything, that allowed them to feel included. The construction of ratiep, with its chanting, rhythmic clapping and drum beats held similarities to rituals performed at the homelands of the slaves which ultimately allowed them to some sort of cultural continuity at the Cape.

The ritual of rampie-sny, which is the cutting up of orange leaves on the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The tradition also has its roots in southeast Asia, with scholars attesting that the word ‘rampie’ may have originated from the Hindi word rampa, but somehow its linguistic adaptation was altered to fit the language at the Cape.

The architectural legacy of slavery is evident in buildings like The Castle, Company Gardens, and the numerous wine estates built in the Western Cape. Slave craftsmen also produced old Cape furniture and other items. South African cuisine has been largely influenced by the legacy of enslaved peoples culture, with Indian and Indonesian influences being the most prominent. The names of some South African recipes illustrate the influence of enslaved people on South African culture with names of food, such as sosaties, bredie, curry, bobotie, koeksisters, and tameletjie. C. Louis Leipoldt, an Afrikaans writer and cook, considered Indonesian cooking methods and food customs as the strongest influence on South African cuisine. These traditions were not only brought to the Cape by slave cooks but also by their owners, who usually lived and worked in Batavia before coming to the Cape. The Afrikaans language was born out of creolization used by both masters and slaves in the Cape colony. This confluence of cultures is also evident in Afrikaans being written in Arabic script, which were religious manuscripts known locally as kitaabs. This blending of language and faith showcases the adaptability of the slaves and how their lasting influence at the Cape has managed to endure through generations.

The Lives of Slaves

The social sphere of slaves may have proved to be challenging in their efforts to construct an identity and build a private life, which was likely due to their differing languages and cultural traditions. Family life was difficult for slaves as they tried to form families in order to regain their humanity and self-respect. However, slave parents suffered more as they witnessed their children being abused by their owners. Slaves were not allowed to get married, and life partners could be separated at the owner's whim. Children of slaves could also be sold separately from their parents, leading to disputes between slaves and owners.The families were centered on women, with children usually living with their mother. In Cape Town, they had some opportunities to mix with free people, but they had very little leisure time. Working long hours as a proclamation in 1853 stipulated that enslaved people were not allowed to work more than 10 hours in winter and not more than 12 in summer. Some enslaved people made friends with the Khoekhoe and San, leading to cultural exchanges - in an effort to protect their offspring from the fate of enslavement they had children with them - a move that provoked significant discontent among slave owners. This tension culminated in a legislative change in 1752, when the government sanctioned the practice of indenturing these children until they reached the age of 25.

Slave life in Cape Town was different from rural areas, as both slaves and poorer free people engaged in leisure activities outside the properties of their owners. Activities included gambling, card-playing, cock-fighting, music making, and dancing. Street brawls were not uncommon, and some slaves even drank heavily.

Gendered slave labour

Slavery operated as a patriarchal institution where enslaved women were regarded as perpetual property, often transferred like inheritance. This system allowed slave owners unchecked freedom to fulfill their sexual desires, resulting in a pervasive and uncomfortable reality for these women, who were subjected to exploitation without recourse. Cape enslaved women were valued for their domestic roles and reproduction of future slaves. They were used in embroidery, knitting, gardening, and were also used for their wombs. Despite being entrusted with the maternal role of caring for their master and madam and raising their children, they were denied autonomy and treated as a permanent minor within the institution of slavery. This created a double bind: they were expected to fulfill nurturing roles while being stripped of recognition as adults, mothers, or autonomous human beings.

Enslaved women occupied a uniquely vulnerable position within slave-owning households, often tasked with maternal and domestic responsibilities. In some cases, these women engaged in sexual relationships with their enslavers in hopes of gaining manumission for themselves or their children. However, these relationships must be understood within the framework of coercion, as the extreme power imbalance between master and slave negated the possibility of genuine consent.Court records have registered these problematic dynamics, such as Anthonij van Goa's slaying of Jannetie, an enslaved woman he viewed as his own wife.

Abolition and its aftermath

Slave resistance in the Cape was suppressed by both owners and authorities, who used physical and psychological measures to maintain the master slave relationship. The Company had power of life and death over slaves, with the Justitie Plaats serving as a place of execution. Two slave uprisings occurred in Cape Town: the first in 1808, led by Louis van Mauritius and Abraham van de Kaap, who persuaded 300 slaves to march to Cape Town for their freedom. They were defeated when they reached Salt River. The second uprising occurred in 1825 on a remote farm in Bokkeveld, led by Galant van der Caab, who killed a farmer and threatened to take over other farms. The slaves were captured and Galant was executed, resulting in the Galant uprising.

The economic significance of slavery in the Cape Colony persisted over time, but after the Slave Trade Act 1807, the relationship between masters and slaves changed. Slaves incorporated the discourse of freedom and universal rights into their expressions and perceptions, leading to increased cases of shirking, labor withdrawal, and open resistance. Despite the increase in slave prices, farmers in Stellenbosch could still accumulate slaves, demonstrating the resilience of the Cape's slave economy.

Emancipation arrived in 1834, but it was not immediate. The Slave Abolition Act 1833 determined an apprenticeship period and financial compensation for slaveholders, but the perceived lack of transparency in the compensation process meant that slaveholders hardly had their expectations met. Britain apportioned 1,247,000 to be paid to Cape slaveholders, but compensation could only be claimed in London, contrary to claimants' expectations. The former slave owners campaigned to gain more control of the now free labor force, leading to the Masters and Servants Ordinance in 1842, which set out obligations between employers and employees. In a system built on the colonisation of diverse nations, it was clear that this law, like other laws, favoured the employer over the workers and was regularly revised and made stricter during the 19th century in order to ensure control.

Furthermore, laws against squatting made it difficult for formerly enslaved individuals to find land to farm as they did not want enslaved people to become independent, which further highlights the tight control, discrimination, and inequality faced by freed slaves after emancipation. This ongoing suppression contributed to the spatial and economic inequalities that still shape Cape Town today. The legacy of land dispossession, restricted upward mobility, and social marginalisation continues to be visible in the city’s segregated geography and unequal access to resources, revealing how the aftershocks of slavery are embedded in its urban and social fabric.

Despite the city's early infrastructure being built by these diverse groups, the legacy of slavery is rarely acknowledged. Visible reminders include the Old Slave Lodge, the Old Slave Church on Long Street, and the Palm Tree Mosque. The social and physical infrastructure of Cape Town was shaped by individuals who served as gardeners, builders, carpenters, fishermen, nursemaids, and street cleaners. South Africa's cultural diversity today is a result of this history, with elements of language, customs, music, and religion deeply influenced by enslaved communities.

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions