PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

Cape Town's Garment Workers

The Western Cape’s garment industry was once a major economic driver for the region and a sector that was employing thousands of (mostly female) workers. In comparison to other textile sectors around the world, the garment industry in Cape Town got off to a slow start, with blanket manufacturing being its first proper production sector during the 1920’s and 1930’s. Although there was clothing production prior to 1939, the acceleration of apparel, furnishings and industrial textiles only took off after World War II. The last major addition to the industry was synthetic textiles which expanded after 1960.

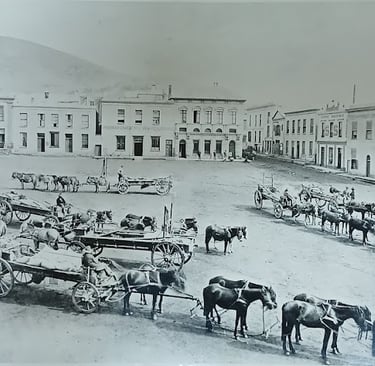

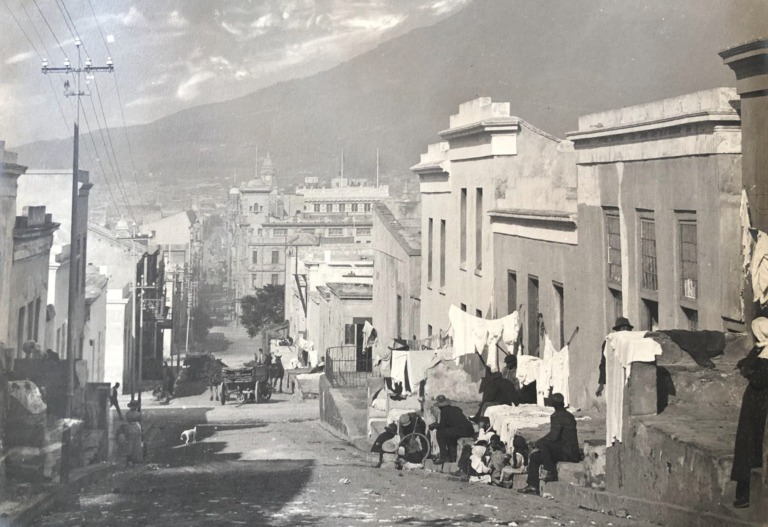

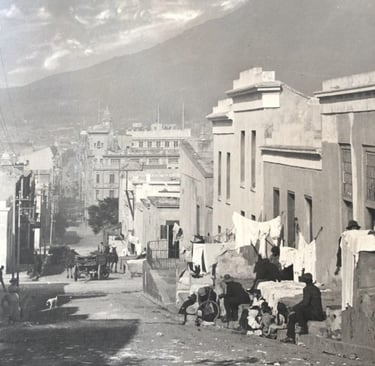

Green Market Square, possibly early 1900’s. The Singer Sewing Machine Factory is second from right. Photo courtesy of Cape Town Archives

Tailors

The introduction of the sewing machine might have been misinterpreted as a means to reduce the work of tailors, however tailors were actually using the ingenuity of the machine to expedite their work and to process larger orders. In actuality, they were able to produce a better quality garment for a lower price by using the sewing machine. Tailors formed the traditional sector within the clothing industry and their work was seen as more high end compared to factory made garments. Tailors therefore, could be referred to as petty commodity producers, as they would employ a small number of workers, or they would subcontract work to middlemen or provide work directly to home workers. In essence, the tailor merged artisanal skill with small-scale production in an emerging capitalist market, therefore, he was self employed but still had some dependency on the capitalist system.

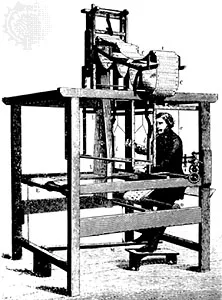

Engraving of Jacquard Loom. 1874

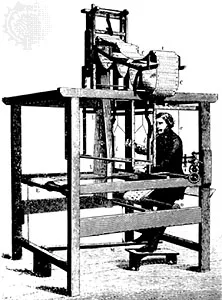

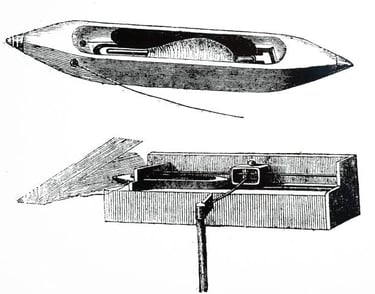

Flying Shuttle engraving. 1851

It's fair to say that the industrial revolution benefited the textiles industry in more ways that one could imagine; the cotton mills housed machinery from the flying shuttle (1733) to the jacquard loom (1804) which enabled faster weaving. Machinery interventions during the 18th and 19th centuries did not have a tremendous impact on hand labor even though they replaced handloom weavers, but ultimately, most of the work was done by factory workers. These workers have remained the backbone of the industry for almost two hundred years. In the western Cape, the garment industry proved to be a formidable force that has left an indelible mark within the economical and cultural sphere of Cape Town.

During the early days of clothing factories, there was little competition between tailors and factories as factory production fell mainly in the market of cheap clothes production, producing for the every day man and women. On the other end of the spectrum the upper classes in the Cape during the mid 1800’s relied mainly on Coloured seamstresses and Malay tailors for their clothing as this was a custom product, crafted meticulously.

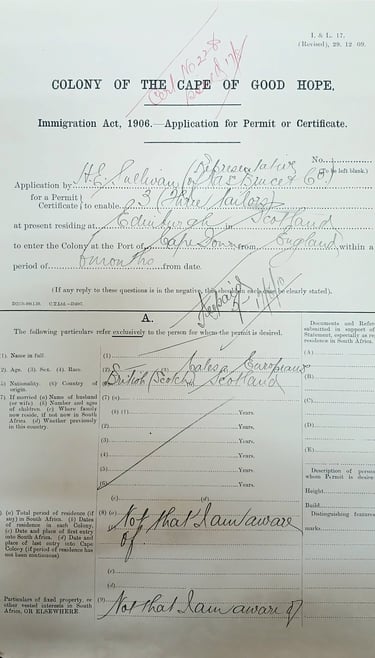

Immigration papers for three tailors from Scotland to enter the Cape. Dated 1910. Courtesy of Cape Town Archives

Records show that in 1906 there were around 200 Malay tailors in Cape Town and they were mainly employed in making trousers and vests. As the economy expanded the Malay tailoring trade used the burgeoning clothing industry for expansion and to integrate itself into the economy. By 1912 there were already 151 tailor’s shops in the city, with a few relatively in close proximity to each other at the eastern ends of Caledon and Longmarket streets. These shops were close to the CBD which meant that client and tailor could have frequent interactions in the construction of the garment.

Malay Quarter, Cape Town (Bo-Kaap), early 1900s. Courtesy of Cape Town Archives.

During the 1930’s the number of white tailors started to decline which meant that Malay tailors started to outperform them in terms of production. Due to their ability to form close relationships with other tailors, it became increasingly difficult for factories and the Wage Board to enforce their regulations on the Malay tailors. The aim of the Wage Board was to ban all homebased and subcontracted work, which seemed to be making no headway. Then in 1932, when much stricter rules were enforced, the tailors banded together to form the Malay Tailor’s Union to tackle these new regulations. Strong in numbers, and with the new regulations not being enforced properly, the Muslim tailors efforts proved successful and in 1938 the Wage Board relented and the tailors continued to work independently from factories and continued with their outwork.

City Engineer papers pertaining to a submission from Mr Omar to erect tailors work rooms in South Road, Wynberg. Dated 1935. Courtesy of Cape Town Archives

Salt River

As the industry gained traction, clothing factories started sprouting up in Cape Town during the mid century such as Rex Trueform (1938), Bonwit (1967) and House of Monatic (factory operations from 1951). In the clothing and textile industry there are two integral factors which influence the site of production: proximity to a labour force and to the market. Even though sites such as Paarden Eiland, N’dabeni and Kensington/ Maitland had the capacity to build clothing factories, their placement on the periphery of Cape Town meant that production would be hindered. Salt River, therefore became the city’s ideal location for clothing production. Salt River and its adjacents offered quality labour in the form of white and coloured skilled workers, and the land below Devils Peak (exhausted brick fields) were cheap and flat, which meant factories could be easily erected. Thus, Salt River Main road, Durham Avenue, Shelly Road, and Swift street were showcasing architectural symbols of the garment industry.

Rex Trueform taken from above. 1940’s. Courtesy of the Etienne Du Plessis Collection.

ORAL HISTORY

The Garment Workers

The garment workers were the unseen tour de force behind many fashion houses, and their workforce was varied and complex. The demographic within the factories were majority female workers who worked the production line.

Citty Petersen was one of those workers who undertook different roles in the industry and saw a career spanning over twenty years. She began working in 1962 at Rex Trueform in Salt River as a learner machinist and after working for a few years she qualified as a machinist in 1965. In 1968 she left the company and joined the Garment Workers Training School in Woodstock in the early 1970s as a training instructress where women underwent a six-week training program in machine operation and garment production. The training school collaborated with various factories to upskill workers, which at the time saw a demand for workers as the industry steadily grew. She highlights that wages were set by GWU (Garment Workers Union) standards, which is formulated around collective bargaining.

The industry was a magnet for employment, and especially to those who felt marginalized by the apartheid system and employed workers from across the Cape peninsula.

“...most of the workers came from as near as Bo-Kaap, Cape Flats, which would be Athlone, Silvertown, Bokkmakierie, Bonteheavel… and further afield”.

Citty left in 1988 as cheap Chinese imports led to downsizing and factory closures. She describes witnessing the unraveling of a once-thriving industry and the emotional impact of that decline. Citty describes the collapse of the industry as deeply sad, affecting livelihoods and community stability.

“...there was concerns because of the cheaper goods coming in and the people doing CMT (cut, make, trim) could not compete price wise and were left with no orders or very little which was not sustainable and they had to close down. And also the very big companies were feeling the pinch and were laying off people and eventually factories started closing down.”

Many former workers moved into retail (Pick n Pay, Shoprite) or cleaning work. Yet, she concludes with hope — quoting “’n Gam het ’n plan” — reflecting the resourcefulness and determination of those affected.

ORAL HISTORY

Independent dress makers

In addition to tailors and factory workers, there were also the independent entrepreneurs in the form of dress makers which were prevalent during the early 20th century. These were skilled individuals who made garments to fit ranging from slacks to wedding dresses. The profession afforded women the opportunity to work from home whilst still being with their families, thereby having a hold on managing the household and still being able to afford some income. On a societal level, it also afforded women to not challenge expectations on gender roles, where they were expected to be home, care for families and not be competing with men in public. Dressmaking therefore, seemed as the perfect venture to explore as it was served for women, by women.

Latifah Adams (93), was a dressmaker during the height of the apartheid regime who managed her business on both spectrums of the old and new South Africa.

“‘My mother was a dressmaker. I was still very young when she died, but that made me interested in it. I went for a course in drafting, pattern-making, and grading. By that time, I could already sew a little, and that’s where I started”. Latifah completed her dress making course at American Academy of cutting and designing, where she graduated in 1965.

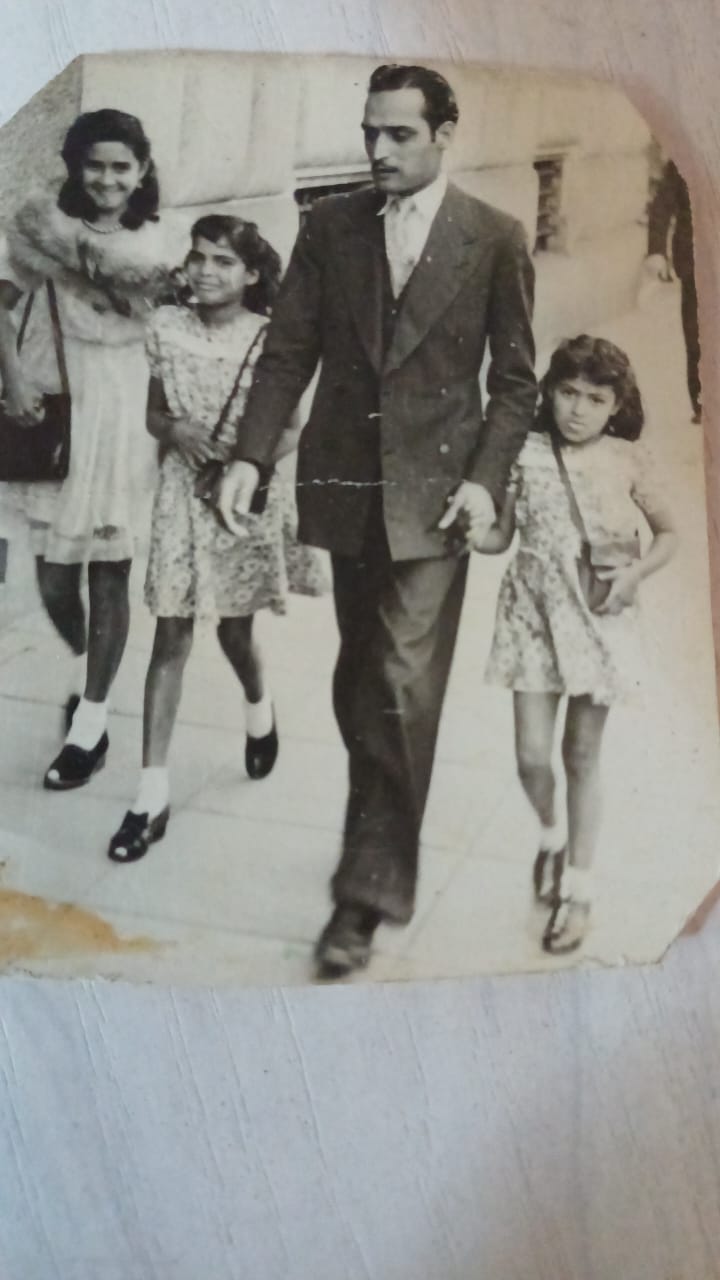

A young Latifah Adams (far left) and her brother Hassiem, who was a tailor and taught her some skills.

“I worked as an independent dressmaker from home. It was in Penlyn Estate, but before that I also worked from Roger Street in District Six, at 91 Roger Street. I had a living room and bedrooms there; I did all the cutting in one of the bedrooms and the sewing in the living room. My clients were not only from the neighborhood but also from other towns such as Muizenberg, Mouille Point, Sea Point, and Goodwood. They came from different racial backgrounds — all kinds of people”. She tells us that her husband was a taxi driver, and many of his white clients came from those areas such as muizenberg and the Atlantic seaboard, and would tell them that his wife was a dress maker, which is also how Latifah got her varied mix of clientele.

Regarding her working style, she states: “I set my prices depending on how long it took to complete a garment and what the work required. For that time, I thought my wages were fair, although by today’s standards it would not be. Things were different then. The customers brought their own materials and I didn’t go out to buy fabric myself. I worked alone; I didn’t employ anyone or have family help. I also didn’t feel any competition from the larger garment factories or imported clothing”. The fact that she was not deterred by the country seeing imports from overseas, or by the large factories pays testament to how these skilled individuals were revered in their communities.

“People didn’t look down on me for being a dressmaker. In fact, I was quite well known — people respected my work”.

“Apartheid laws did affect my business. Some of my clients from Green Point and Muizenberg were white, and they couldn’t come into our areas easily. They were often afraid to come, and it made things difficult, but none of them were ever arrested. There were times when business slowed down — during the riots, for example, when it became unsafe and people stopped coming into the area”. Even though white clients could move around freely (freedom of movement), and could come into District Six, it wasn't so easy for non-whites. Her daughter laments on the sad reality of the removals saying that their opposite neighbours in Rogers Street were one of the first families to go as their homes were bulldozed. After that, they stayed two more years before moving saying:

“ The neighbours were gone, the shops are gone, there were tractors all over the place…They just bulldozed your house. They (the residents) were given a notice, but where were people to go to? Where must they go…”

In reality, there were places to go, however the Cape flats seemed an alien concept to those who built their entire lives around community, around friends and family. So just as the residents of District Six saw their homes being razed to the ground, not long after, the garment industry started splitting at the seams, and by the early 2000s was already a distant memory.

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions