PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

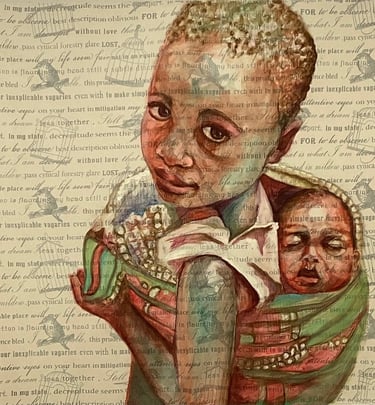

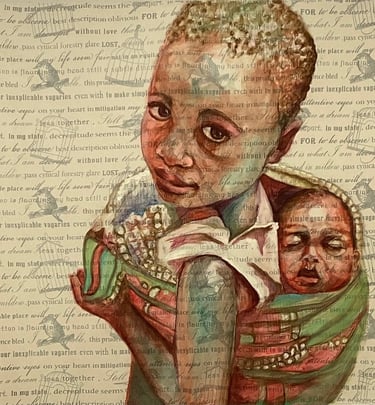

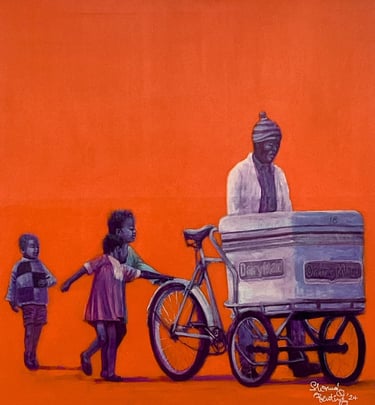

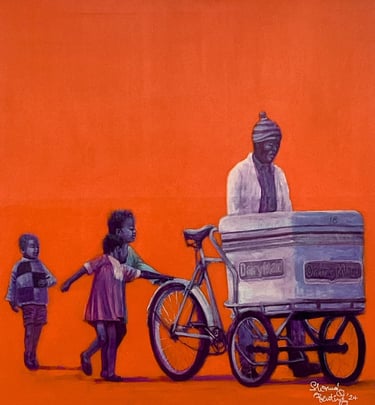

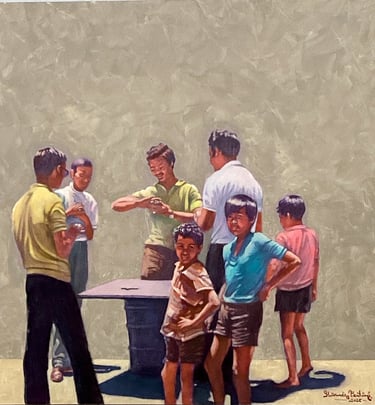

Shaunez Benting: Benting’s artwork is easily recognizable due to his unique and memorable colour combinations. His skill in colour selection sets his work apart from others, having spent the first 5 and a half years in Red Cross Hospital due to eye complications and partial blindness. Benting's work is derivative art which is a mixture of composite pictures and memories that allows him to explore the subject of childhood nostalgia.

The art

A Glimpse Between Memoirs

It was a common practice to secretly meet your person on the shop corner, the rendezvous unfortunately had the additional security of a sibling!

Buskers trying to earn something to feed themselves, entertaining Passersby in 1970s Cape Town...

As a child you are not aware of the surroundings you inherit or the proverbial cards you are dealt with - as you get older you try your hardest to come by on something substantial to remove yourself from that hardship

As children, my friends and I couldn't afford an ice lolly or sucker as we termed it, so we usually just followed the ice cream vendor to just touch the guard on the back wheel....

We used to be fascinated with kids in Carnival gear during the Big days, often going home to stitch our own makeshift garments with scrap fabrics and shopping bags!

A collage depicting the continuation of the Cape Coons from District Six to the CapeFlats...

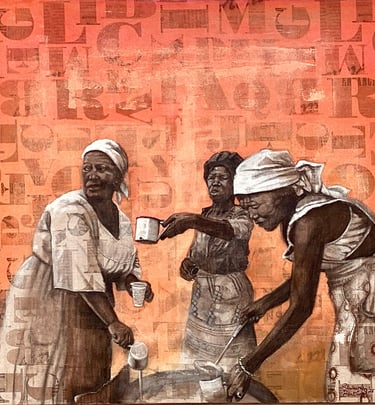

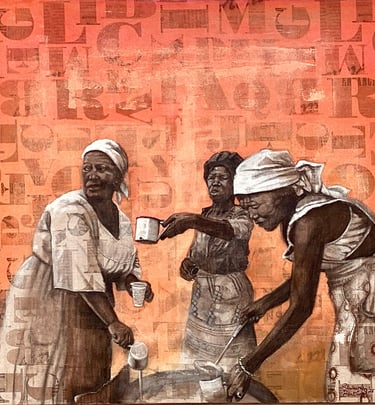

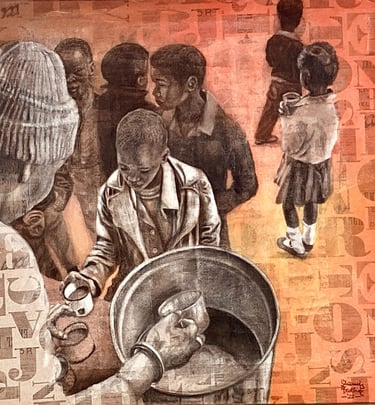

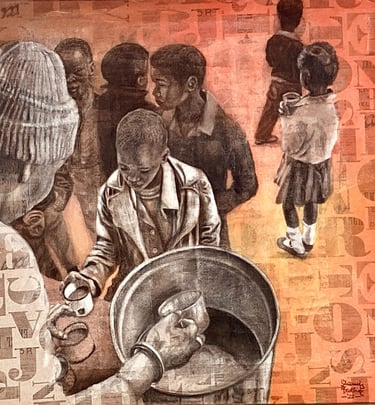

The unsung heroes of our impoverished CapeFlats communities, the silent givers of Hope and nourishment, from the days of SHAWCO: the UCT established Students Health and Welfare Centres Organisation ran various health and education programmes across disadvantaged communities since the 1970s and is still active today as well as many other needed and informal feeding scheme initiatives - the helpers themselves are people, mostly women, who experience hardship themselves...

The rather common game of Dominoes has a long history on the CapeFlats and is a favourite lunchtime pastime amongst the Blue collar factory workforce...

My observation of the maids in the 70s, they usually sat outside the house to enjoy a meagre lunchtime snack, milk and a half unsliced loaf was also an extremely common staple of migrant labourers and black factory workers during the 70s into the 90s...

The art

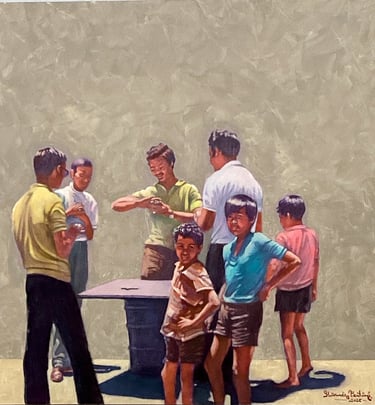

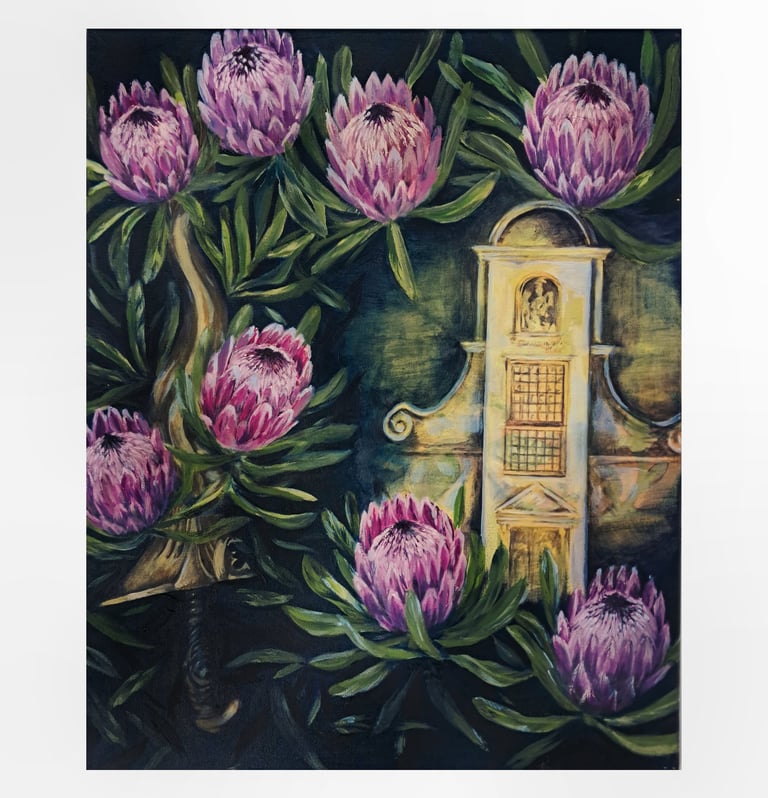

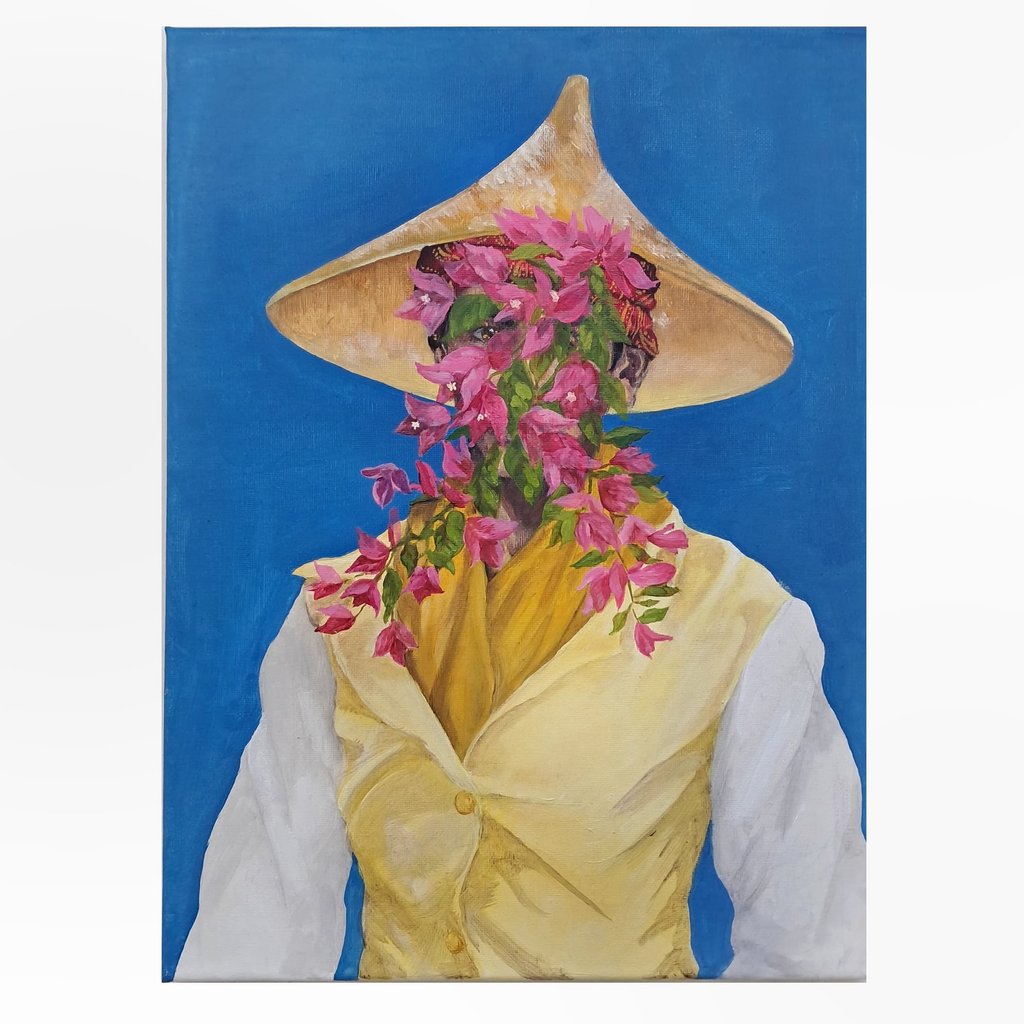

M. Whaleed Ahjum: With an honours degree from Michaelis School of Fine Art, Whaleed Ahjum's approach to art is multidisciplinary with a particular affinity for oil painting. His artistic practice is grounded in research, which involves extensive reading on a given subject before commencing his artwork. Ahjum’s creative process is driven by a yearning for knowledge and understanding.

In reference to the my Melayu heritage, within which, it has cultural significance of citrus in ritual and symbolism, as well as the connection to my maternal family name, . With the intention of evoking the fragrant blooms, the flora obscures the sitter, my daughter, connecting both with a sense of continuation. The Heritage we seek to preserve is as much the generations that will follow after we are long gone.

My grandfather, Achmad Ockards, who drove the nurses from Groote Schuur Hospital out to the Cape Flats weekly to serve as a mobile clinic to outlying community. I never met him and had seen all but two photographs but had grown up on stories of him related by my mother and her siblings. Known among his community for his harness making and husbandry of horses.

Western dress was worn out in public, but many of us grew up with stories of our grandparents donning the lungi and iconic footwear of the Cape Melayu Diaspora. I grew up being told of my grandfather who would fashion his own kaparangs and the sound of clacking raised soles being heard when he would perform his ablutions for morning prayers.

The colonial architecture of the Cape Dutch homes is often associated with Cape heritage. Groot Constantia is often regarded as the epitome of this style and era, being the residence of the first Governor of the Cape colony, Simon Van Der Stel. During his tenure, my ancestor was “banished to the forests of Constantia”. The Keris, stands for his presence and subsequent life there, obscured by time and overshadowed by colonial and later apartheid narrative.

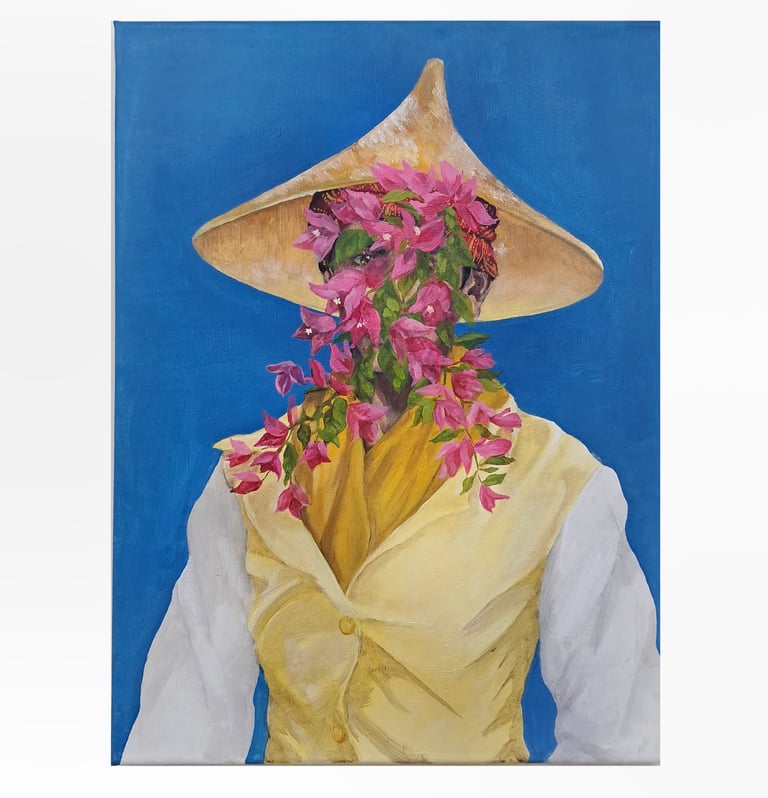

Historical depictions of Cape Malay individuals often them garbed in western dress and often as flower sellers. The tradition was often passed on in families based jn Constantia, which continued until their displacement under Apartheid. Illustrations detailing their appearance from western artists are the only visual references, until the advent of photography. Based of one such archival print the figure portrayed is concealed by the hibiscus, a flower so widespread in the Cape, it is almost unremarkable, despite its origins, like those descended from the displaced individuals from Malacca and Nusantara, have taken root here. The hibiscus, the national flower of Malaysia—being the former seat of the Malaccan Sultanate— is shown against a batik inspired protea motif, underscoring the connection between the locations and peoples.

As with The Lady of the Blooms, the figure's depiction is based off archival illustrations and photographs. The iconic headgear, the concave conical reed hat, the tudong was identified with the Melayu diaspora present in the Cape. Rarely identified other that “Malay” we never get to know their names. Just as the hibiscus, the Bougainvillea sprays are so widespread they're near commonplace in Cape Town. So the diaspora is seen as part of landscape, but more importantly part of the land.

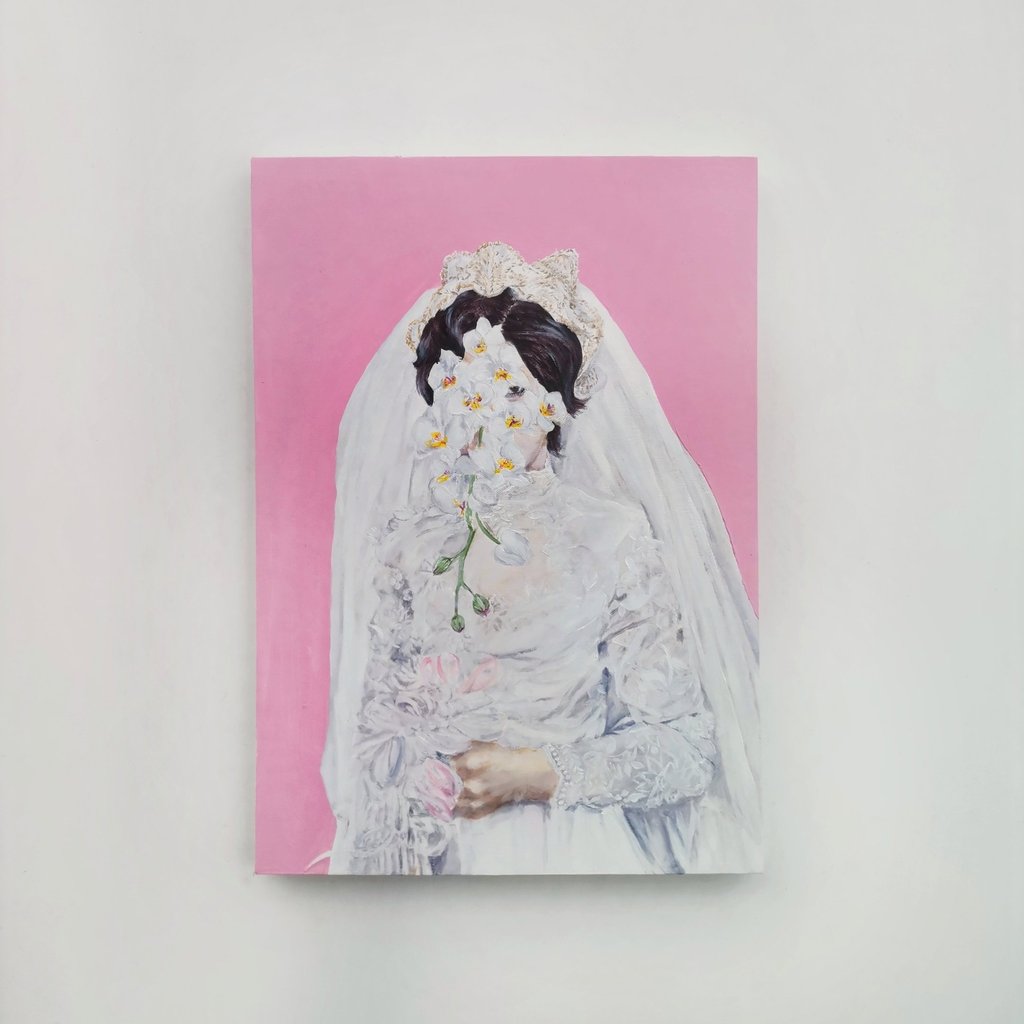

Indonesian orchids were my mother's favourite flower. She felt an affinity towards them as they linked her to her heritage. According to the family oral tradition, we are descended from one of the first three political exiles, taken from Soesoerang Castle and exiled to the Cape of Good Hope, in the Constantia forest, kept from the general population for fear of raising insurrection.

She, her family and community, retained their connection to Malaccan and Nusantaran Straits, now Malaysia and Indonesia, through cultural practices. A large part which was connected to citrus, spice and floral natural heritage, relegated to mere "resources', by their colonial occupiers. The scent of citrus leaves and perfume of orchids were links that rooted the displaced Diaspora to their homelands. My mother would tell me how she ordered her wedding bouquet to be centered around the Indonesian orchids and there would be a mournful note to her voice as she would say "they are where we are from."

She instilled a sense of justice and refusal to allow injustice to prevail. To always stand against oppression, as we always have. She taught me about art, principles of design, that no matter what an oppressor can take from you, there are two things they can never take; your knowledge & and dignity. So enrich yourself with education for the first and never give away the second.

The figure's hand rests upon the hilt of a Keris, or Kris, a dagger which would serve as modern western rings do today. Up to three would be worn, one given by one's father when one came of age, one denoting rank or status, and one which was presented by the father of their wife- the decoration on the pommel would correspond to a buckle worn by her around her waist. Similarly to the Yemeni Jambiya, the owner would never be without a Kris. As these were all plundered by the invading European companies, their value as social, cultural and individual identifiers were lost on them and simply regarded as mere weapons.

According to our oral family history, we are descended from Sayed Mahmoud. Brought to the Cape of Storms as a political exile: the religious advisor to his fellow exile and Sultan, Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah, named the last Sultan of Malacca (Melaka) after an arduous battle held at Soesoerang Castle. As the last of the court of Melaka they posed a notable threat as a rally point for revolt against the invading colonists and so were taken to the distant forests of Constantia. His Kramat, or Mazaar, stands atop Islam Hill. The title is taken from the inscription at his mazaar.

Ockards , who was so named for the orange orchards which they were once stewards in Kimberly, South Africa. First arriving in the Cape as political exiles from the Malay archipelago for resisting the Dutch colonial entity of the VOC. Their descendants ended up moving north, to Kimberly, where a stone pillar stands to commemorate the Malay Camp. There they came to be charged with caring for an orange orchard; a reminder of their heritage, with lemon and citrus being an essential part of their culture. The Keris, a dagger with undulating curves, once worn by their men would be maintained and cared for by rubbing the damascene blade with lemon leaves, imparting the aroma and oils to clean and protect the blade and held over burning frankincense and myrrh - or miyang and lobaan - the the resinous smoke would scent the blade and deposit a protective sheen all while reciting protective verses from the Qur'an.

Disarmed, for obvious reasons, the trace was retained in the tradition of the Moulood an Nabi, the commemoration of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) and upon departing from the ceremony, then held in secret, the men would receive Rampai or Rampies, silk packets of cut lemon leaves, doused in rose water to be placed in one's clothes chest or wardrobe which would scent the clothes and deter pests. They retain the aroma and would be replaced in the passing of the lunar year till the next Moulood.

Upon the death of the master of the orange farm, so impressed with their character and care with which they treated the citrus trees, he left the family [vir kind en kinderen] the estate; asking that they take name Ockards to ensure the claim. The land, seized under Apartheid, is no longer theirs, but the name remains. A connection to their roots, their past and traditions.

Inspired by the Indonesian Green peacock; though less well known than its cousin from the Indian subcontinent. The stately bird is placed before the batik inspired motif of stylized cloves and clove buds.

Batik, the wax resistant textile art, originates from what is now Malaysia and Indonesia. After colonization of Malacca, Nusantara and the surrounding islands, the craft was industrialized and production was brought to Africa and carried out by slaves to export to Europe. The wax printing tradition has taken on it's own form in Africa - one result is what is now known and marketed as Shweshwe, a far departure from the undulating floral motifs of its origin

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions