PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

NADIA KAMIES

PORTRAITS

Nadia Kamies, writer and academic author on the subject of “coloured” identity shares her personal family archive. The personal portraits serve as a time capsule, capturing the essence of what it meant to be a person of colour in a former era and the intricate ways in which this history intertwines with one's sense of self. It meticulously documents the stories, struggles, and triumphs of those who navigated a world coloured by prejudice and discrimination, offering a poignant glimpse into how experiences of the past continue to shape and inform our present identities. As we delve into these preserved memories, we are reminded of the resilience, dignity, and spirit of community that have long been hallmarks of the "coloured" experience, inspiring us to honour the past while charting a course towards a more inclusive and equitable future.

The preserved portraiture images by Nadia Kamies intricately capture the narratives, challenges, and victories of individuals navigating a world tainted by bias and inequality. These images offer a poignant insight into how historical encounters continue to influence our present identities. Portraiture remains a potent medium, serving as profound historical artifacts that narrate the tales of past societies while shaping the trajectory of history and culture. Initially appearing as mere depictions of individuals, a closer examination reveals invaluable clues that assist in unraveling compelling historical stories.

Portraits not only functioned as a form of defiance against colonization but also as a cultural weapon against segregation. Kamies's photographs stand as invaluable historical reservoirs. With a discerning focus on the past, she frequently discovers inspiration and enlightenment in history, drawing upon the teachings and experiences of bygone epochs. The personal family archival photos and portraits act as a visual representation of culture through time and serve as a cultural memory, offering valuable and insightful information about history, about ancestors and about connections. Nadia Kamies sharing her personal memories helps us comprehend the past along with the values and norms of the “coloured” experience. It additionally generates a sense of collective identity and is a way of conveying a cultural heritage to individuals who are unfamiliar with it.

A Creative Heritage

My grandmother’s doilies are a recurring theme in my writing. The simple objects that were created by her hands and that my mother thought important enough to keep and pass on to me, give me a sense of belonging. They provide a way to fill in the blanks in the official records and help me to piece together a narrative of who I am and where I come from.

Modern crochet, or “poor man’s lace”, was invented as a cheaper alternative to the lace that the wealthy used to adorn their garments. These skills were passed down within families and amongst friends, and was often a way for women to supplement the family income.

I started experimenting with the doilies in the clay classes I attend, imprinting them into the earth, rubbing oxides into the grooves and layering them with slips and glazes, as a way of interpreting my grandmother’s past creativity and situating it firmly in the present. The resulting set of vases and bowls preserve her work for her greatgrandchildren.

When I found an art certificate that my father received in 1954 for a hand-drawn design of one of my grandmother’s doilies, I imagined the links running between all three our projects, chainstitches interlacing three generations.

These simple objects hold cultural memory that connect us to each other and help us to tell our stories. They are imbued with history, language and memory and hold the imprint of human touch and experience. They form part of an archive of the ordinary that disrupts the narrative that we are a people without a history.

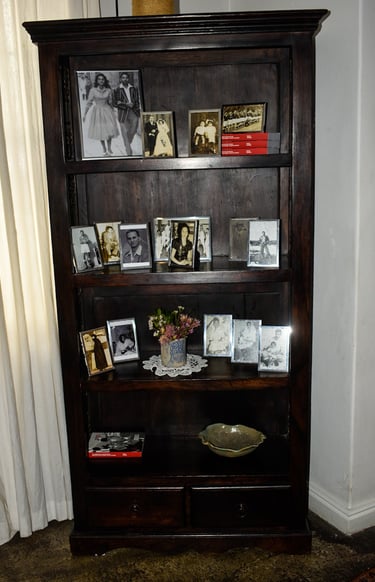

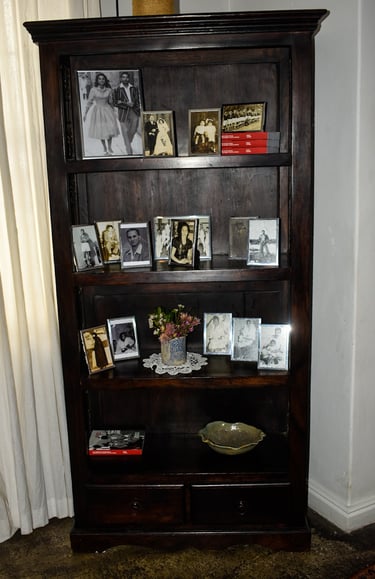

Family Photographs

In the absence of a recorded history, family photographs have served as memory aids helping me to access the stories that bear witness to what it means to be named and understood as “coloured” in a democratic South Africa. The humble images found stuffed into albums, chocolate boxes and biscuit tins, often off-centre and out of focus, are tangible objects that link us to each other and to objects over time and space.

The introduction of the Kodak camera in 1888 democratised the taking of photographs, allowing ordinary people to take control of how they were represented and providing an invaluable record of the daily life of families and an invitation to reconsider oppression.

Often, the photographs were taken on special occasions when we were dressed in our “Sunday best”. They challenge stereotypes, introducing new knowledge and ideas and dimensions of meaning. They operate as repositories of memory, both personal and cultural, facilitating the construction of the past, situating it in the present.

Why did people go to such lengths to take photographs of themselves at their best, of laden tables and new possessions? Were these acts of defiance, a silent challenge to a government intent on subjugation and humiliation? Or was there a sense of the future in their performance, a need to make sure that their stories were told? At the very least, the subjects of these photographs silently but defiantly assert: we were not what they dictated we should be.

Portraiture

The two portraits of my father and aunt and my maternal grandfather were commissioned separately by my grandmothers in the late 1930s and 1940s, respectively, while they were living in Woodstock. I am intrigued by what motivated them and I’d like to think that this was their attempt to gain control of how their families were represented in a society that sought to brand them as inferior.

Airbrushed portraiture was introduced to South Africa in the late 1930s from Chicago. Travelling salesmen would visit communities all over the country, from urban townships and rural villages to big cities, where clients would hand over their precious photographs. The photos would be enlarged, printed and then coloured in. The portraits were given similar backgrounds, obliterating the context in which the photographs were taken and, in a sense, democratising them, deeming where you came from as irrelevant.

The portraits convey a negotiation of respectability, telling stories that may be passed down and spoken about and their subjects validated, seemingly protected from exclusion and inferiority. They defy the subjects’ designation as second-class citizens, disrupting the official apartheid narrative of what it meant to be “coloured”. They force us to reflect on how the oppressed were represented.

Find out more about Nadia's portraits on our Instagram page where OCTH completed a weekly feature around her personal family archive...

Copy QR Code to easily share

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions