PRESERVING CAPE HERITAGE AND CULTURE THROUGH EXPLORING VISUAL ARTS AND EDUCATION

A Heritage of Common Humanity

"If slavery and apartheid was about degradation of the human being, being free to re-create ourselves, drawing on a vibrant and diverse culture, honours the spirit of survival and resistance of the people from whom we are descended."

THROUGH YOUR PEN

Nadia Kamies

5 min read

A Heritage of Common Humanity

The identity document I was issued with during apartheid in South Africa designated me as a ‘coloured female’. The official government definition for ‘coloured’ was “a person who wasn’t white or a native”. ‘Coloured’ was a catch-all category used to describe a diverse group of people - heterogeneous in skin colour, language, religion, and culture - who are descendants of Europeans, enslaved Asians and Africans, and indigenous people of the Cape. It was used for anyone who didn’t fit neatly under the apartheid definition of ‘white’ or ‘black’.

My maternal grandmother, who was from a rural town outside of Cape Town, was Christian and spoke mainly English (unless she was talking about something she didn’t want us children to hear, then she switched to Afrikaans). My father’s mother, on the other hand, had always lived in the city centre, spoke Afrikaans and was Muslim. The apartheid government had classified them “Cape Coloured” and “Cape Malay”, respectively. My two grandmothers lived roughly on either end of Hanover Street, the main artery running from the city centre through District Six where my paternal grandmother lived, to Walmer Estate where we lived with my maternal grandparents. As a child I traversed this space regularly, negotiating the space between English and Afrikaans, Christianity and Islam, between a poorer District Six and a better off Walmer Estate.

District Six, where my father was born, was declared an area for “whites only” in 1960 and, over the following two decades, a once vibrant area made up of the descendants of freed slaves, merchants, immigrants, artisans and labourers, was reduced to rubble. My memories of this area are of a rich diverse culture of food, music, language and religion, that emerged through a process of creolisation of the European, African and Asian influences at the Cape.

The Dutch, who arrived at the Cape in 1652, laid the foundation for racial segregation and apartheid in South Africa. Their arrival was followed six years later by slaves from the coast of Guinea and Angola, India and South East Asia. They were forced to work in the kitchens and vineyards of their masters, in a system that was violently controlled. As happened in other parts of the world, slaves were stripped not only of their homes but also of their identities, religion and culture when they arrived at the Cape.

Enslaved people inhabited two worlds – the one that was approved of by their masters and a hidden one where they could develop relationships with one another and develop their own culture based on their different origins and traditions. By the end of the 17th century the liaisons between the indigenous people, the African and Asian slaves and the Europeans had given rise to a mixed population. Official discourses rejected suggestions of creolisation, ethnic interaction and cultural exchange between different groups of people. The vibrant and diverse cultures that arose out of the dehumanising legacy of slavery and racial subjugation, speaks to the spirit of resistance and will to survive that is the essence of what it means to be human.

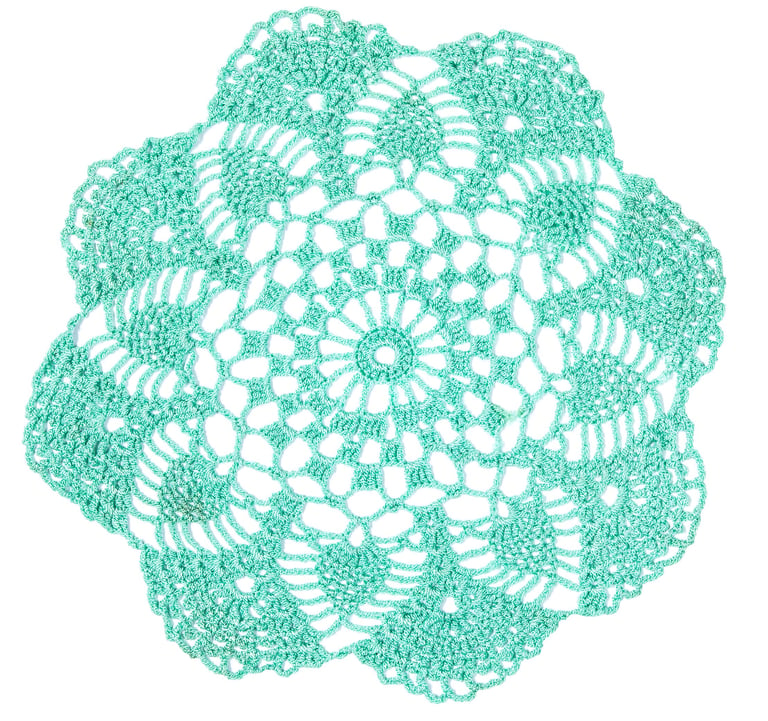

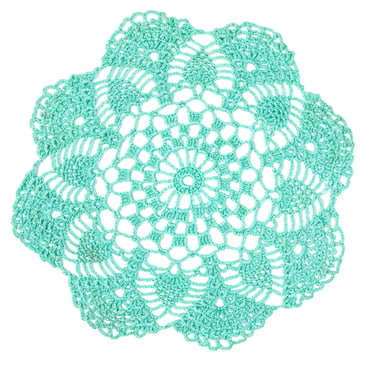

Humans have always created objects of beauty to adorn themselves and their homes; these objects capture and express different ways of living and being. Both my grandmothers were skilled at handcrafts and embroidered, knitted, sewed and crocheted. These creative endeavours were rooted in the culture of their homes and communities. The skills were learned amongst themselves and passed down from one generation of women to the next, in many cases providing a way of earning a living and thus a sense of empowerment. There are records of enslaved women at the Cape listed as seamstresses who were occasionally allowed to earn modest sums of money. The American abolitionist, evangelist and women’s rights activist, Sojourner Truth, a former enslaved woman herself, was famously photographed with her knitting resting on her lap, almost as a symbol of her own emancipation. Truth taught these handicrafts to freed enslaved women as a means of supporting themselves.

During apartheid the oppressive regime attempted to silence people, and art became a weapon for political expression, reflecting the injustices and repressive nature of the times. Ironically, the arts – music, dance, painting, story-telling and so on – the very practices of what makes us human, flourished. People continued to find way to communicate and express the injustices of the day, telling the stories that the world needed to hear. Their work so disrupted and threatened the apartheid hegemony that many were arrested, banned, or forced into exile.

Cape Town artist, Dr Peter Clarke (1929–2014), described his work as a reflection on humanity, on a commonality that surpasses all boundaries. He was a former resident of Simon’s Town whose family was forcibly removed to the ‘coloured’ township of Ocean View after the Group Areas Act was passed into law, assigning people to different residential areas based on their ‘race’.

“My art is about people and the presence of people. The humanistic image is what interests me. I enjoy reflecting on people and their activities, their emotions, what could be events in their daily lives. But beyond that I speak via my symbols of activities on a larger, wider scale that transcends all boundaries…. I speak about a heritage of a common humanity.” – Peter Clarke, 1983

If slavery and apartheid was about degradation of the human being, being free to re-create ourselves, drawing on a vibrant and diverse culture, honours the spirit of survival and resistance of the people from whom we are descended. This cultural heritage shapes our identities and help us to understand ourselves – where we come from and where we are headed. They not only celebrate our achievements but may facilitate the healing of our communities. They help us to move beyond the process of othering, to a place where we may think about how we may live together.

People make culture. Interpreting and defining our everyday experiences is how we make sense of the world. The seemingly simple handcrafted objects that my grandmothers made are infused with history, language and memory; they are imprinted with the human touch and experience and they help us to write a different narrative of who we are and where we come from. This is my creative heritage, a heritage of common humanity.

Copy QR code to share easily article

Discover

Contact Us

Our cultural heritage matters

Help us learn and grow by sharing your respectful feedback on our website, exhibitions, social media and more:

Store's Terms and Conditions